by Marie Snyder

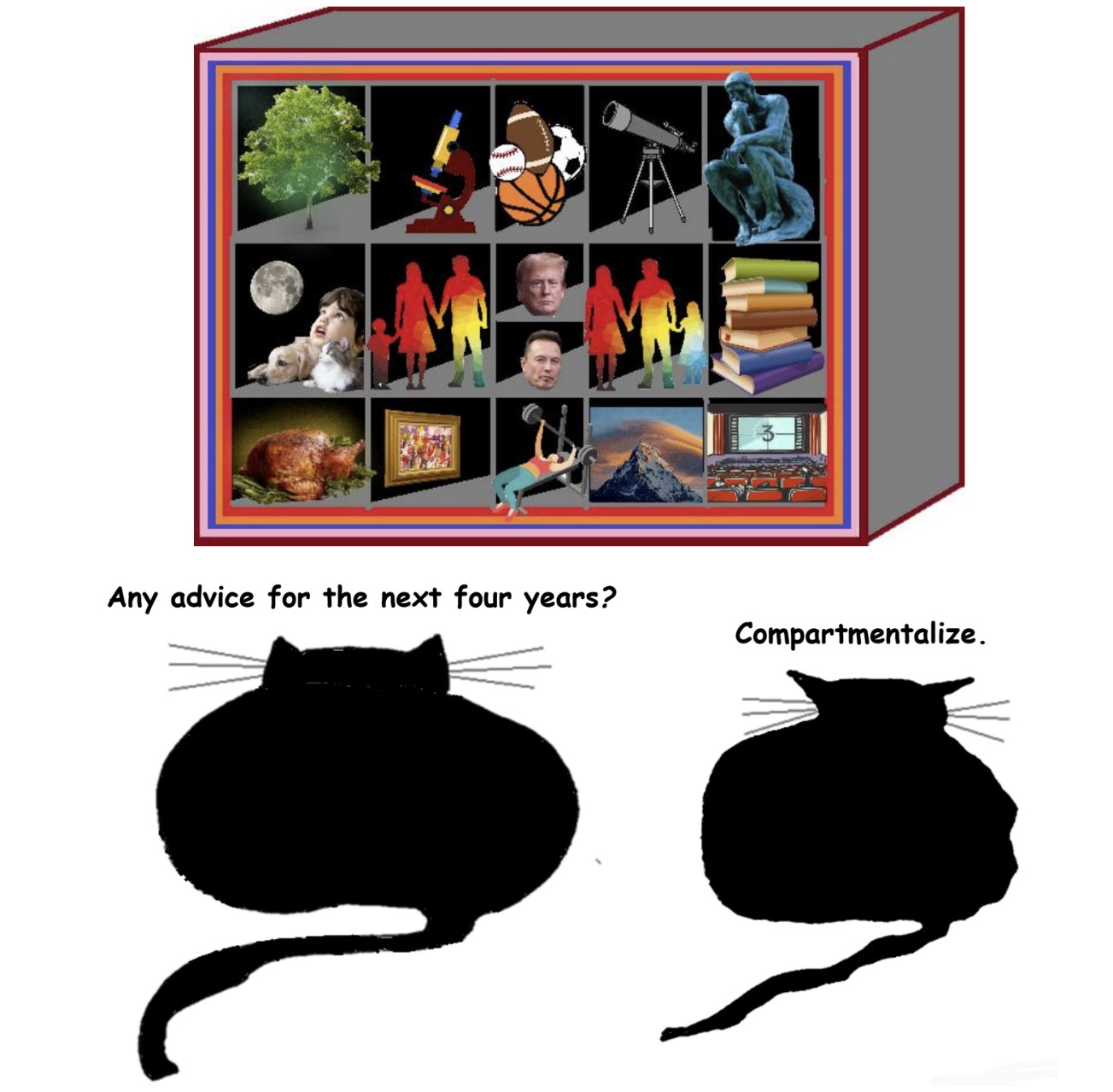

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

I dipped my toe into Stoic Week again this year. I’ve done it before a decade ago, and even went to StoicCon once! I was hoping to find the attitude necessary to manage all this (gestures broadly at everything). I got stuck on the first day.

They start with Epictetus’s bit on figuring out what we can control and what we can’t:

Some things are under our control, while others are not under our control. Under our control are conception [the way we define things], intention [the voluntary impulse to act], desire [to get something], aversion [the desire to avoid something], and, in a word, everything that is our own doing; not under our control are our body, our property, reputation, position [or status] in society, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing.

It’s from the Encheiridion, or handbook, which is a short read and pretty accessible.

I get the gist of it. A lot of the time when we’re bothered by something, we can’t control what’s going on in the world, but we can control our attitude towards it. It’s only bad because we think it’s bad. The thing to do in all cases is to act virtuously because that’s all that’s within our control. Comedian Michael Connell explains the stoic attitude in an analogy about late trains. If we’re in a hurry, news of a late train is a tragedy. But if we’re stuck on the tracks, it’s fantastic! But in the face of Covid, climate change, and the many conflicts around the world, how do we shift this news to be anything but horrific? The only perception that can spin it as good seems to be genocidal in nature.

So maybe I’m overthinking it, but I have questions about what Epictetus specifically says here.

First of all, how is desire under our control? I can’t control what desire to have or not have, but I can notice it and decide what to do with it if I have my wits about me. If I’m tired, then sometimes even my behaviour feels not remotely within my control. With practice, I think we can reduce the intensity of some desires or desensitize ourselves from aversions, but desire is pretty automatic. We desire or are repelled in an instant. Epictetus is calling on us to do that practice every day, but it only gets us so far. Even just being able to take a beat to consider the situation is a challenge when we’re overwhelmed with demands on it. Read more »

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

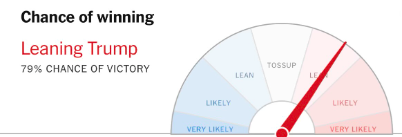

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

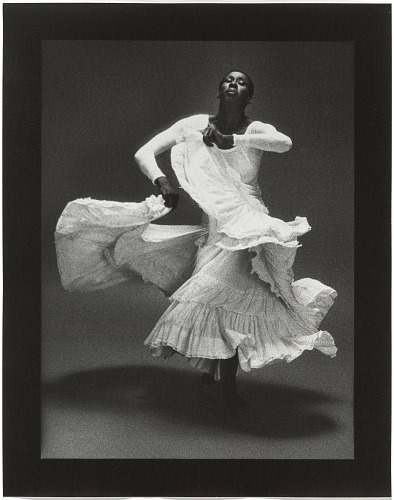

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election. Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.